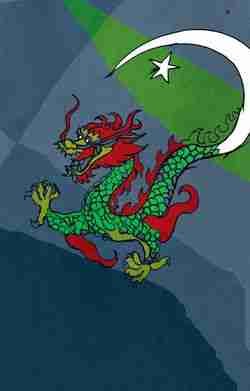

In The Dragon’s Eye

The military drubbing India received from the Chinese 50 years ago still rankles many of us as many of our army units, despite being ill-clad and barely equipped for war, had fought back ferociously, sometimes with their bare hands and stones when ammunition ran out. Their defiance in the face of imminent defeat is the stuff of legend. At Namka Chu, near Thagla ridge, where it all began, 7 Infantry Brigade under Brigadier J.P. Dalvi (of Himlayan Blunder fame) was massacred despite the heroic stand of units like 2 Rajput, which were virtually wiped out by the Chinese. Among all this, clearly the honours for the “last stand to the last man” goes to Major Shaitan Singh (a posthumous PVC) and his 114 men of 13 Kumaon, at Rezang La, near Chusul in Ladakh. They repulsed seven Chinese attacks till they all died holding their weapons, and lay frozen there for weeks.

So it wasn’t for a lack of determination by our forces. The fall of Tawang, Walang, Se La and Bomdi La could perhaps have been prevented if only India’s military brass hats in Delhi and Tezpur had stood up to Nehru’s arrogant defence minister Krishna Menon—who had once boasted that he alone could handle the Chinese—and prevented him from micro-managing the conflict. The odd ones who did, like Lt Gen Umrao Singh, GoC 33 Corps, were marginalised and a new corps was raised in Tezpur to accommodate New Delhi’s man, Lt Gen B.M. Kaul. But once the Chinese attacks began, it was clear Kaul was out of his depth. He soon took ill but insisted on commanding his forces from a hospital bed. Though China’s aggression of 1962 lasted only a month—October 19 to November 21—it has left scars that are yet to heal. The reason is that the causes of India’s defeat—largely in Se La and Bomdi La on the eastern front, and in Aksai Chin in the west—have been hushed up, and the nation hasn’t had a chance to understand who all were guilty for the debacle.

After the war, the new army chief, Gen J.N. Chaudhuri, ordered Lt Gen T.B. Henderson Brooks, a second generation Indian army officer, and Brigadier (later Lt Gen) Prem Bhagat, VC, to find out what went wrong. But as the government clearly didn’t want to fix responsibility on individuals, their report was restricted to mundane tactical issues like training, equipment, physical fitness of troops and the role of military commanders. Moreover, even if Brooks and Bhagat had wanted to, they had no access to records of meetings in the MoD, as Krishna Menon had categorically disallowed any notes or minutes to be kept of his conferences, saying these were top secret. But they still produced an unforgiving analysis of the problems along the entire Sino-Indian border and squarely blamed army headquarters for its direct interference. However, this report lies locked in a vault in South Block on the misplaced fear that it could further sully Pandit Nehru’s reputation. It has apparently (by one account) been accessed by Jaswant Singh, the historian Neville Maxwell, and some others at the defence ministry’s historical division, tasked to research and write the official history of the 1962 conflict (which is yet to be made public).

Interestingly though, we learnt another lesson 25 years ago. While the use of the Indian air force in 1962 was limited largely to ferrying casualties (an offensive role was curtailed for fear of escalating the conflict), in 1986, General Sundarji used the IAF’s heli-lift capabilities to respond swiftly to a Chinese build-up at Sumdorong Chu, to move troops north of Tawang and across the Namka Chu—where the Chinese began the 1962 invasion—to stare down the Chinese. While Rajiv Gandhi felt India must back off, Sundarji refused to so. He apparently offered to resign, saying, “Please make alternate arrangements if you think you are not getting adequate professional advice.” The Chinese eventually pulled back. Herein lies a lesson on how to deal with a belligerent China. And although India is today militarily well placed to defend itself, the bigger question is: does India’s political leadership have the nerve to look the Chinese in the eye? The answer: perhaps, no. To that extent, we are where we were 50 years ago.