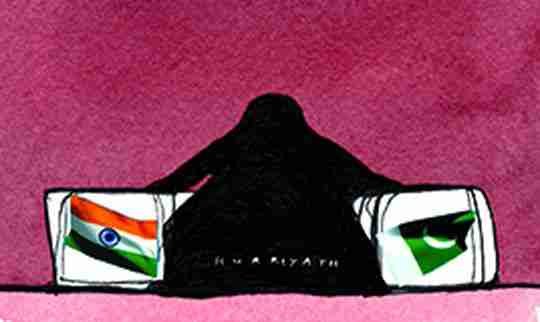

Choose your side, world

In a welcome move, New Delhi has called off the talks scheduled between foreign secretaries of India and Pakistan on August 25. Since 1999, Pakistan has been led to believe that despite the most brazen attacks on India― the Kargil conflict and the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai are cases in point―talks would be revived and it would be diplomacy as usual. No wonder then that Pakistani high commissioner Abdul Basit ignored the warnings of Foreign Secretary Sujatha Singh, and went ahead with his meeting with the Hurriyat, a Kashmiri separatist group.

Clearly, the Pakistanis had decided to follow their earlier practice of humouring the Hurriyat―a non-elected, self-styled group of largely anti-Indian Kashmiris―to openly dismiss the objections of New Delhi. Their disregard for India’s current stance―that Pakistan could talk to either the Indian government or the Hurriyat, but not to both―was based on their past experience, when the Indian government had meekly complained, and then let things be. Though, ironically, the Congress that led the UPA government had often taken credit for the Shimla Accord (which, among other things, was meant to keep Indo-Pak relations, especially Kashmir, a bilateral issue), by allowing the Hurriyat to interact with the Pakistanis, they had allowed this third party a role. The Narendra Modi government has rightly called their bluff.

In fact, even before being elected, Modi had made known that ‘talks and terror’ cannot go hand in hand. And, his recent speech at Ladakh was an indicator that India’s policy towards Pakistan would hereafter be different, even though many peaceniks were thrilled at Nawaz Sharif’s presence at Modi’s swearing-in. In reality, within Pakistan, there has been an ongoing turf war between Nawaz and the increasingly assertive new army chief, General Raheel Sharif, who, along with his army brass hats, is opposed to Nawaz’s desire to improve relations with India. Therefore, the visit by Nawaz for Modi’s swearing-in took place after some behind-the-scenes lobbying by Nawaz’s team with the army brass.

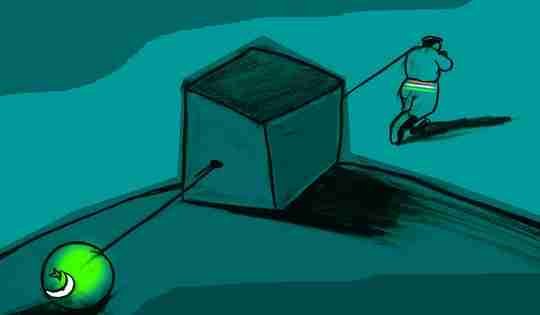

But India apart, tensions between Nawaz and the army were already high over how to deal with the Taliban―Nawaz wants dialogue, the army wants to hit them―and on the treason trial of General Pervez Musharraf. The army says he has been humiliated enough. Nawaz, it appears, is already beginning to fall in line, as he is also faced with nationwide discontent and big political challenges.

In fact, Pakistan could soon be sliding back into its past, with the army in charge. Nawaz will thus have to let his generals do what they are masters at―revert to their anti-India, fight-to-the-finish stance over Kashmir. Having tried and failed in all their efforts to capture Kashmir militarily, they will still keep at it, since giving up on the Kashmir ‘issue’ would be seen as a defeat. And, as the Pakistan’s army operates on predictable lines, we could witness more terror attacks coupled with the rise in Pakistan’s nuclear saber rattling―both by their proxies, terror attacks by jihadis and nuclear threats by their ‘experts’ in the media―all targeted at bringing pressure on India (especially from Washington) to begin talks again.

But not talking is also a diplomatic option for India. The world―especially the US―must be told to choose between India and Pakistan. The US refused to engage with Iran for decades and made sure others didn’t, too. And those countries that wish to engage with Pakistan―a sponsor of terrorism―should then be denied access to Indian markets. India’s markets are now a big attraction for the western economies and China, and they must choose whose side they are on.